This website is dedicated to enhance our knowledge of the English language as ESL & EFL, promote the free sharing of documents, resources, materials, etc with a special focus on Mexico´s NEPBE or PNIEB, but at the same time, provide articles, material, resources that are of national and international interest.

Thursday, December 12, 2013

Can I learn English in 18 months?

Here´s a very interesting article written by Luiz Otavio Barros, and it deals with the issue of the time in which a person can become fluent in English, I recommend you to read it.

Monday, September 16, 2013

10 Tips to Improve Behavior Management

1 Be in charge.

As

the teacher, and the adult, you are ‘in charge’. It is your classroom and you

must actively and consciously make the rules and decisions, rather than letting

them happen out of habit, poor organisation or at the whim of the pupils.

Demonstrate

your ‘in-chargeness’ by the position you take in the room; keep on your feet as

much as possible and be where you can watch everything that is going on. Pupils

should be convinced you have eyes in the back of your head! Pick up the good

things they are doing (see number 3 below). Keep moving around the classroom to

establish yourself as the focal point of interest and authority.

Remember

that the pupils need to feel safe; they can only do this if you are in charge.

Do not justify or apologise for your rules, your standards or your insistence

on compliance.

2 Use positive classroom rules.

Pupils

need to know what is expected of them in your classroom. Establish a set of

rules, no more than 4 or 5, which make desired behaviour explicit; display them

prominently in the room and refer to them frequently so that they don’t

disappear into the wallpaper!

The

rules should tell the pupils what to do, rather than what not to do, eg

O Don’t call out.

P Put up your hand and wait

to speak.

O Don’t walk around the classroom.

P Stay in your seat.

O Don’t break things.

P Look after classroom

equipment.

Praise

good behaviour and refer to the rule being followed. Use the rules to point out

inappropriate behaviour, “Remember our rule about …”

Have

a ‘feature’ rule now and again, written on the board and tied to a special

individual or class reward to be given to pupils who follow the rule.

3 Make rewards work

for you.

Give

pupils relevant rewards for desirable behaviours, starting tasks, completing

tasks, following class rules, etc. The goal is to establish the HABIT of

co-operation. Standards can be subtly raised once the habit has been

established. The easiest, quickest and most appreciated reward is descriptive

praise.

Other

possible rewards, besides those used as a school-wide system are:

- a note home to parents

- name on a special chart which earns a later tangible reward

- being given special responsibilities

- being allowed to go first

- having extra choices

4 Catch them being

good.

Praise

is the most powerful motivator there is. Praise the tiniest steps in the right

direction. Praise often, using descriptive praise, for example, ‘It can be

annoying having to look up words in the dictionary. I can see you are getting

impatient but the dictionary is still open in front of you. You haven’t given

up.’ Or, ‘I can see you don’t want to come in from break, but you are facing

the right direction for coming in.’ Be willing to appreciate the smallest of

effort and explain why it pleases you.

Pupils

will not think you are being too strict and will not resent your firm decision

making if you remember to smile, to criticise less and to praise more. Tell the

pupils there will be positive consequences for positive behaviour, then follow

through and show them.

Stick

to your guns and don’t be ‘bullied’ into giving rewards that haven’t been

earned.

Some positive behaviours are easily overlooked.

Try to remember to praise pupils for:

- homework in on time

- homework in late but at least it’s in

- working quietly

- good attendance

- neat desk

- not swinging on chair

- smiling

- contributing to class discussion

- helping another pupil

- not laughing at another pupil’s mistakes

- promptly following your instructions

- wearing glasses

- using common sense

Use

the reward systems of the school consistently and fairly.

5 Be specific and

clear in your instructions

Get

a pupil’s full attention before giving instructions. Make sure everyone is

looking at you and not fiddling with a pencil, turning around, looking at a

book, etc. Only give instructions once; repeating can unwittingly train a pupil

to not bother to listen properly the first time. Smile as you give

instructions.

Don’t

be too wordy and don’t imply choice when there actually isn’t a choice by

tacking ‘Okay?’ on the end, or sound as though you are merely suggesting,

‘Would you like to …?’ ‘How about …?’

‘Don’t you think you should …?’

Be

very clear in all your instructions and expectations. Have a pupil repeat them

back to you.

6 Deal with low level

behaviours before they get big

Low

level, or minor, behaviour infringements will escalate if they are

not

dealt with quickly and consistently. A pupil’s behaviour is reinforced

when

he gets attention for it, but don’t be tempted to ignore it. Find a

calm

and quiet way to let the child know that you see exactly what he is

doing

and that there is a consequence, without making a fuss, getting

upset

or sounding annoyed.

Give

your instructions once only. If the pupil continues to misbehave, instead of

repeating your original instruction, try one or more of these actions:

- point to a place (eg on the board, on a post-it in the pupil’s book, a note on your desk) where you wrote down the original instruction at the time you first gave it

- use a description of reality, ‘Alfie, you are tapping your ruler.’

- stop everything and look at the pupil pointedly and wait for them to figure out why

- descriptively praise those who are behaving appropriately, praise the target pupil as soon as he complies

- ask other pupils what is needed (the squirm factor)

Always

follow through, even on minor infractions, so that pupils know there is no

point in testing. They should know what will happen. Only give second chances

after a period of good behavior.

7 The consequences of

non-compliance.

Help

the pupil to do whatever you’ve asked him to do. If he has thrown pencils on

the floor, help him to pick them up.

If

a pupil does not obey instructions straight away, do not give up. Keep waiting.

Praise every little step in the right direction, even the absence of the wrong

thing. For example, if you’ve just asked a pupil to stand up and he’s not doing

it, you could say, ‘You’re not swearing now, thank you.’

Do

not protect the pupil from the consequences of his action or lack of action.

The pupil is making a choice and you will have told him this, and given a clear

warning of the consequence.

A

consequence should be uncomfortable and not upsetting enough to breed more

resentment. The purpose of the consequence is to prompt the pupil to think, ‘I

wish I hadn’t done that.’

Have

a ready repertoire of easy to implement and monitor consequences. These might

include:

- loss of choices (eg where to sit)

- loss of break time

- loss of a privilege

- sitting in silence for a set amount of time

8 Find a ‘best for

both outcome’.

Avoid

confrontational situations where you or the pupil has to back down. Talk to the

pupil in terms of his choices and the consequences of the choices, and then

give them ‘take up’ time.

‘Fred,

I want you to leave the room. If you do it now we can deal with it quickly. If

you choose not to then we will use your break time to talk about it. It’s your

choice. I’ll meet you outside the door in two minutes.’ Then walk away and

wait.

‘Joe,

put your mobile phone in your bag or on my desk. If you choose not to do that

it will be confiscated,’ then walk away and wait.

9 Establish ‘start of

lesson’ routines.

Never

attempt to start teaching a lesson until the pupils are ready. It’s a waste of

everyone’s energy, giving the impression it’s the teacher’s job to force pupils

to work and their job to resist, delay, distract, wind up, etc. Often this task

avoidance is a ‘smoke screen’ hiding worries about what you are going to ask

them to do.

Have

a routine way of starting a lesson; a quiet activity that pupils can get right

down to, without needing any explanation. Handwriting, copying the lesson objectives from the board, spelling practice (familiar key language from the current

topic), mental arithmetic are good activities to set a quiet tone. Do not allow

discussion or be drawn into discussion yourself – say there will be time for

that later and make sure you follow this through.

If

you take the time to establish this, lessons will start themselves! You won’t

have that battle at the beginning of every lesson to get yourself heard.

10 Manage the end of

the lesson.

Do

not run your lesson right up to the last minute and then have to rush because

the next class is waiting. Allow time to wind down, answer questions, put

equipment away, refer to WILT and how this has been met, outline plans for next

lesson, etc.

Have

a short, educational game up your sleeve if there is time to spare.

Manage

the pupils’ exit of the room, have them stand behind their chairs and wait to

be asked to leave. Address each pupil by name and have them tell you some good

news about the lesson, or you tell them something they did well today. Send

them out one-by-one.

Great site with lots of posters with quotes about teaching!

Great posters with quotes about teaching which have been incredibly popular, so in this website you´ll find lots more of them.

Download them FREE now from http://www.teachingideas.co.uk/more/management/contents_staffroomquotes.htm

Friday, April 5, 2013

Academic Writing: Process and Product

This publication deals with different aspects of academic writing and its teaching, including that of essay writing, project writing, scientific writing, writing for examinations, and article writing.

http://

8 Myths About English Fluency: Part I

What is fluency and what’s the best way to teach and learn it?

From my teaching practice I realize that the majority of my attitudes and beliefs about fluency and language learning were based on popular misconceptions generated by people who knew very little about reaching fluency.

Not only were they completely wrong, but these ideas were counterproductive to my own language learning and teaching, leaving me frustrated, confused and stagnant. I realized that my success as both a language learner and teacher would depend on me opening my mind and developing a new perspective.

The first thing I had to learn as a language learner and English teacher was separate fact from fiction, which meant abandoning my own false ideas that no longer served me or my students.

MYTH 01- FLUENT SPEAKERS DON’T MAKE MISTAKES

ADVICE: RELAX AND MAKE LOTS OF MISTAKES: COMMUNICATION > GRAMMAR

There´s a popular idea that fluency is a magical land of perfect grammar, native-like pronunciation, and unobstructed communication.

The truth is that fluency is none of these. The truth is that few people, if any (including native speakers) speak with perfect grammar, and nearly 99.9% of people who learn English as a second language will always have some sort of accent from their native language. Learn to accept this and be okay with it. You can work to smooth it out, but your accent is your cultural identity, and this isn’t a bad thing.

Good language learners learn to communicate first (or at the same time as they learn grammar), and they work through their grammar and pronunciation problems on a parallel basis or after. Mistakes will surely happen when you open your mouth, but this is the path to fluency. The baby doesn’t learn to walk by crawling. She falls and falls A LOT.

MYTH 02- FLUENCY COMES WHEN YOU LEARN ALL THE GRAMMAR

ADVICE: YOU SHOULD CULTIVATE PIECES OF FLUENCY FROM THE START

Another popular misconception, which goes hand in hand with Myth 1, is the idea that fluency is a distant reality that will come one day when you’ve learned enough English grammar.

It’s okay to expect fluency in the future and big advances in your grammar, and this is sure to happen with diligence and hard work, but you can start finding the courage to attempt small everyday pieces of fluency right now. Theory and practice should go hand in hand throughout the entire process. If you are not learning to use the grammar you learn now, you will probably forget it later.

Successful learners are able to cultivate fluency from the very beginning in specific situations. If you know only know how to introduce yourself, learn how to do this with confidence by doing it a lot, whenever, wherever, and with whoever you can. Learn basic survival English, how to say hello and goodbye, and start thinking about every grammar lesson you learn as something you will apply the next day.

This will be a big shift in your attitude that will help with everything else, bits of fluency that will not go away. It’s almost as if you are writing a script for a play that you will act in over and over again.

Every situation has an opportunity for fluency, and the first thing you should focus on are everyday situations. Fluency is not just an abstract long-term plan, but a daily opportunity that you can cultivate.

The more real life situations that you find, such as an English language learning community or group and making English a part of your daily life with Lifestyle English, the easier and more interesting your experience will be.

MYTH 03- YOU MUST STUDY ABROAD/ BE IMMERSED IN IT TO GET FLUENT

ADVICE: MAKE YOUR LIFESTYLE A CONSTANT ENGLISH IMMERSION

A study abroad/ English exchange program can be an amazing learning experience, a big help for fluency, as well as a great pleasure for your life, but it’s not a magic pill for your failures at home nor a must for reaching fluency.

There are a lot of people who believe such an experience to be the solution to all their English problems. They often buy into the myth, spend a lot of time and money going, only to come back disappointed by not having learned much English.

If you have the time and resources and are a self-directed learner, I would also recommend trying to plan backpacking trip and finding schools or programs independently as you go along. Nothing is better than meaningful cultural adventure that will grant you social and linguistic opportunities. If you want to speak English the entire type, it might be a good idea to travel alone or without other people from your country.

Even if you don’t leave your home country, fluency can be closer than you think if you adapt the proper lifestyle to support an enjoyable, consistent process that enables you to live your life through English. In this way, you don’t even need to study because you it’s part of your life and you experience it with enthusiasm.

MYTH 04-YOU NEED A CERTIFICATE/EXTERNAL APPROVAL TO BE FLUENT

ADVICE: USE CERTIFICATE EXAMS TO COMPLIMENT FLUENCY, NOT DEFINE IT

Fluency is not an external piece of paper, nor the approval of your friends or workmates. You are the only one who can decide if you’re fluent. If you need these external validations for your own personal sense of fluency, you probably haven’t developed the confidence, clarity and courage to really be okay with your level.

Receiving a piece of paper that shows you learned how to take a standardized test won’t fix that. Only real life use of the language and contact with the culture can give you a sense of personal ownership (i.e. fluency) over the language you are using.

While these tests are great and useful for giving a certain integrity and balance to your process and measuring your progress in some of the more technical areas, don’t confuse the guidance tools for the essence of your own personal sense of where you are and what you need to do.

There are plenty of people armed with a test score that gives them a sense of false confidence about their English level, while not knowing how to communicate spontaneously in a real life cultural situation that calls for them to respond in the most human and personal of ways.

CALL TO ACTION

Your call to action today is to consider and reflect upon your beliefs and attitudes toward English fluency. Do you have a good idea of what fluency is? Do you know what it feels like? Are you entirely committed?

And what about myths and preconceptions that might be damaging your language learning process? Have you abandoned the garbage that holds you back? Challenge yourself to become a better language learner and not except mediocrity.

7 Qualities to Maximize the Impact of your Lessons Plans

There are obviously many, many things that teachers can do to maximize the chances of an individual lesson going well. This tip shares just a few elements that research (and personal experience) tend to say are important. It is not designed as a universal checklist for teachers to ensure that every lesson they do includes every characteristic listed. On occasion, some successful lessons might not include any of these qualities. Other times, some teachers might include most of them.

Strategic Introductions

A strategic introduction to a lesson includes several aspects:- Novelty: Grab students’ attention by introducing information, a topic, or a lesson in a different way.

- Relevance: Provide explicit suggestions on how students will be able to transfer what they learn into other aspects of their lives.

- Written and Verbal Instructions: When students forget what to do, teachers can then just point to the instructions instead of repeating them.

- Modeling: Explicity model your thinking process, and show students examples of other students' work.

- Activate Prior Knowledge: Remind students of how what they are going to learn relates to what they have previously learned.

- Translating: Ask students to "translate" important concepts into their own words.

Movement

Creating opportunities for students to move—at least a bit—during lessons can be successful. Students could move to be with a partner for a quick "think-pair-share" activity, or go to a small group to work on a project for a longer time.Choices

Choices can include being asked for their partner preferences, allowed to choose which reading strategies they would like to demonstrate, invited to choose where they would like to sit during small group sessions, or given two or more options of writing prompts.Minimize Lecture & Maximize Cooperative Learning

Studies show that smaller groups work best, with three or four students being the maximum. I personally prefer sticking with pairs for most of a school year, and possibly moving to three near the last quarter after six months of student experience with the process.Wait Time

The average time between a teacher posing a question and a student giving the answer is approximately one second. Multiple studies show that the quality and quantity or student responses increases when the wait time is increased to between three and seven seconds.Fun

Games are good tools for review, and can function as a quick three-minute break or transition time.Feedback

It has been found that if students are expecting to receive "rapid" feedback—a teacher's verbal or written response shortly after the work is completed—the quality of student work increases.Thursday, April 4, 2013

ELT Ideas too good to be taken seriously

The idea: Gamification, that is the use of games or elements of gaming to enhance the language learning experience.

The problem: Often taken too literally by teachers to mean any game in class or misrepresnted by publishers and reduced to ‘listen and click’ style flash games which fail to appeal to today’s PlayStation/X-Box gaming generation.

How it should be done: Let’s face it - a school student who fills his/her free time with the likes of Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto (however age inappropriate) is hardly going to be enticed by the prospect of being instructed to click on the red balloon, find the hidden star or color the puppy yellow, is he or she?

This game aims to bring together target language and the type of games your students love to create a truly engaging listening experience. The student takes the role of either a mob hitman, a secret service sniper or a rogue agent (always important to offer them choices) and sets himself/hersefl up in a camoflagued location overviewing a crowded scene such as an enemy army camp, a political rally or a meeting of the local mafia.

Instructions are then received from the mysterious unseen ‘commander’ via the shooter’s earpiece like this:

“Can you see the short, fat, bald man who is wearing a green jacket and sunglasses? Shoot him in the leg.”

Or…

“Locate the red building. That is where they store their fuel. Hit it with an RPG.”

Or even…

“You see the boss’ wife? She’s holding a white puupy. Make it red!”

There is also the opportunity to recieve corrective feedback:

“Great shot! He won’t be walking for a while.”

Or…

“I said the RED building! You hit the oranage building - that’s the canteen where they eat lunch.”

Students of course have the opportunity to level up, receive new weapons and earn promotions. Topics to be covered potentially include colours, buildings, descriptive adjectives and, of course, parts of the body.

In order to avoid too much controversy, for very young learners, a version will be available in which the shooter uses a paintball gun as is instructed to splatter the given targets with different colours.

Would students enjoy it? Absolutely

But would it work? Alas, this one is destined to never make it intoı an ELT publisher’s catalogue. Parents, teachers and the media are likely to ignore the instense contextualised language practice on offer in a format similar to games we let kids play anyway to focus on the ‘controversy’ of it all…

IELTS: Tips for the Reading Section

Do I need to read the whole text first in IELTS is one of the more common questions. Put briefly, it is a very good idea to do this. There are four reasons for this:

- Some question types require you to read the whole text (think of the paragraph/heading matching question for example).

- Reading and understanding the whole text helps you to make intelligent guesses about answers you are not sure about

- You save and don’t waste time if you read the whole text first – you waste time by not knowing which part of the text to focus on

- If you want to improve your reading, you want to improve all your reading skills – meaning that your score may never improve if you don’t learn to skim a text for general meaning.

Practice the skills – 4-3-2

Learning to read a text quickly is a skill and skills take a little time to learn. Don’t expect to learn how to do it immediately. Give yourself a little time. One simple idea is to start off by skimming a text quite slowly – say in 4 minutes. Then, when you can do that, try it in 3. Then in 2. The general idea is that just because you need to skim in around 2 minutes in the exam, does not mean that you need to practise doing that way all the time before the exam.Make notes as you go

If once you have skimmed the text for general meaning, you can’t remember what it was about, that may be a waste of time. So try making notes as you go – this is practical. How you choose to do that will depend on you. You can write, underline or highlight – use the method that works for you.

It still doesn’t work? – skim the questions and title at least

Okay, if it still doesn’t work, then maybe it is not a technique/skill for you. Try it your way. Different learners do differ and I’m always reluctant to say that something must be done one way. I would say though that it can help to read through all the questions first and look at the title of the text – that way you should get at least some idea of general meaning.

Labels:

EFL,

ELT,

ESL,

IELTS,

IELTS material,

IELTS Preparation,

IELTS Reading.,

IELTS Tips,

IELTS websites.,

learning english,

learning strategies,

teaching english,

teaching tips,

teaching training,

TEFL

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

IELTS preparation: where to start – plans, teachers, books and sites

There are many different ways of approaching IELTS. How you go about it will depend very much on the level of your English and the band score you require. However, my experience is that the people who succeed are people who organize their studies well and that means starting in the right place. Here are a few suggestions about how to do that.

Know your level

IELTS is all about getting a score. It really helps to know your approximate level before you start the learning process. That will give you an idea of how long you may need. It is dangerous to generalize as IELTS works differently for different people but….If you are within half a band score, then the process may be quite quick. If you are a full band score or more away, then the process is likely to be much longer and you may need to study in different ways.

How can you know your level? My suggestion is to do two separate reading and listening tests. These you can grade yourself and typically the average reading/listening score will be close to your average score for all 4 modules. I suggest you do two tests because you need at least one test to understand the exam structure.

The best resource here are the Cambridge exam books (below).

Make a study program

Your study program will depend on you. There is little right or wrong here. You just need to work out what is going to work best for you. Here are some details to think about:

All 4 skills together or one at a time? My slight preference is for doing one skill at a time as it allows you to focus more on each skill, but by the time you get to the exam, you need to be doing all 4 at once.

Exam practice and skills/language learning: unless your score is very, very close to what you need, you are unlikely to improve your score enough just by doing practice test after practice test – this means that you want to allow time for general English learning.

How long you study for at a time: this will depend on personal circumstances of course. It can help to study for longer periods as you need to learn to concentrate in English for long periods – part of the problem of test day is that it is very long. But shorter periods of study can be more effective in learning. If you get bored you probably aren’t learning.

Self-study or a study partner: later this year, I will be adding some form of forum to this site. Why? It can really help to work with other people: language is communication and IELTS is a language test.

Find things you enjoy doing: this applies to people who are studying IELTS long-term in particular. If you learn to hate IELTS, the process becomes much harder. The idea is to find language activities you positively enjoy – that way you are much more likely to learn. In the end, IELTS is easy, it’s the language that is hard and you want to remember to learn the language not just the exam.

The one thing I don’t mention here is how long your study programme would/should be. There is too much variation here to give you any sensible advice – it can be weeks, it can be months – sometimes it can even be days! I will say this though be realistic and think about your motivation

Some standard advice is that it can take up to 6 months to improve half a band score. Scary? It helps to be realistic and to understand the problem. One way to deal with it is to think beyond IELTS and to study English for its own sake – that’s much more fun and, in the end, you are taking IELTS to use English in an English speaking country.

Books

Websites can be good, but so are books – particularly fort organised learning. There are any number of good IELTS books. Here are a few of my special recommendations for people studying by themselves. These links will take you to Amazon (I’ll add that there is no affiliation!)- The Cambridge Exam Books: you want to get at least one of these books for the most authentic practice. They are by no means perfect as they give you little or no help in training. They test, they do not teach. Don’t overdo them.

- Insight into IELTS: this book is not the regular course book. Rather it looks at each paper/skill separately. For me this makes complete sense.

- IELTS writing skills: writing is the skill that many/most candidates stress about. This is a super book and I can also heartily recommend almost any IELTS book written by sam McCarter. He’s good.

- 101 and 202 for IELTS: I see that there is now 404 too (which I haven’t used). These books are slightly different again as the focus in more on hints and strategies – closer to the typical internet experience.

- Grammar and vocabulary for IELTS: For me, these two are easily the best IELTS grammar and vocab books on the market. (I dislike the red vocabulary book). They are in many ways just general vocabulary and grammar books (that’s IELTS), but all the exercises are in context – meaning that you get useful exam/language practice at the same time.

Websites

There are nowadays 100s and 100s of IELTS websites out there. I started this site about 6 years ago as a a wiki for my personal students to show them the best places (not always the easiest places to find). You can still visit my directory of great sites (not all IELTS sites – but that is the point), but here is a short form version:

- IELTS org: you need to visit here to understand the test format and formalities. At the vey least you should download the candidate booklet

- British Council: they help make the exam. Their preparation materials are very professional – the only downside to this site is that is slightly dull.

- BBC Learning English: this is the ultimate English language learning site. If you need persuading, the sort of language you will find here is exactly the sort of language you need for the exam. I particularly recommend Words in the News.

- ELC: a huge site with very generous resources and excellent suggestions for exam preparation

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Using Pictorial Representations To Teach Rules Of Grammar, Punctuation, And Word Usage

Amused by the misplaced modifiers in your students’ writing? Frustrated that your students omit commas in direct address? Tired of explaining the difference between your and you’re to your students?

Try explaining these often-confused rules of grammar, punctuation, and word usage through pictorial representations. In this article I have shown how five tricky concepts can be explained pictorially. I have tried them and they work!

How to Teach Rules Of Grammar, Punctuation, And Word Usage Using Pictorial Representations

- 1

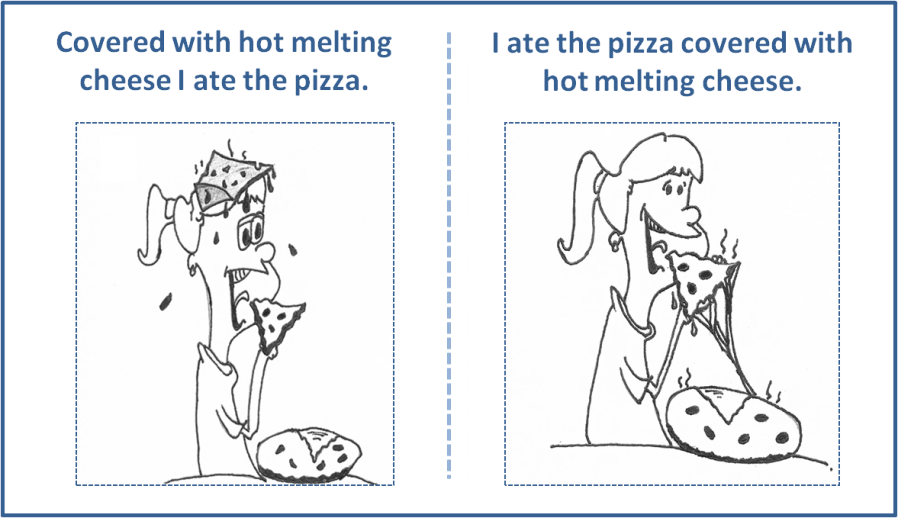

Misplaced Modifiers

Misplaced Modifiers can cause considerable confusion to readers and can also be a great source of amusement to them. The error caused by misplaced modifier can be depicted pictorially through many humorous examples. One of them that I use is shown below.- By way of explanation, I use these points:

- Modifiers are like teenagers – they fall in love with whatever they are next to. Most misplaced modifier errors can be solved by placing the modifier next to the word or group of words that it seeks to modify.

- In the first sentence, covered with hot melting cheese (the modifier) seeks to modify pizza and not the person eating it. Placing the modifier closer to the word pizza clarifies that the pizza, and not the person eating it, is covered with hot melting cheese.

- 2

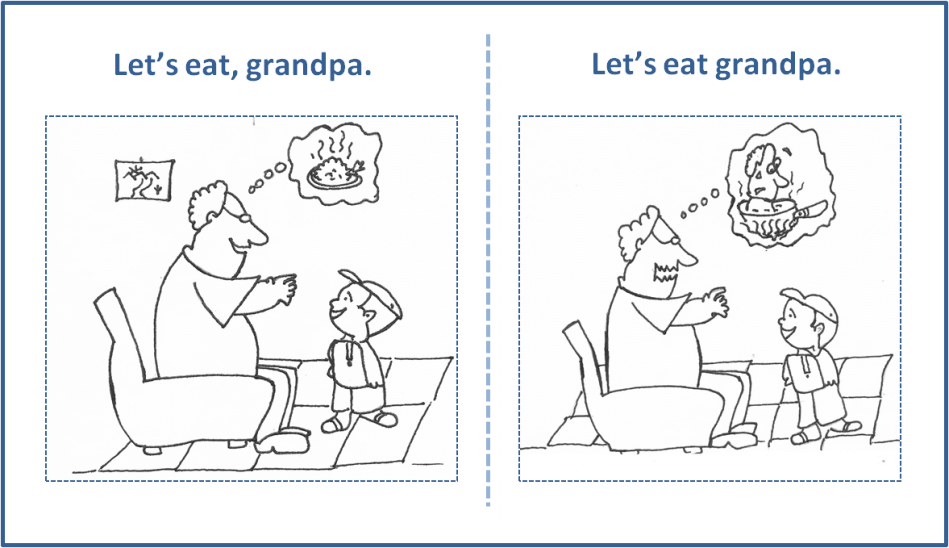

Comma In Direct Address

Not using commas in direct address is a very common error. Students and adults alike commit this mistake. Show them the picture below and they will develop an appreciation of the importance of using commas correctly in direct address.

- By way of explanation, I use these points:

- Placing the comma before grandpa clarifies that the boy is asking his grandpa to eat with him. Without the comma placed before grandpa, it would appear as if the boy wants to eat his grandpa.

- Commas are used to set off names (or words used in place of names) when addressing people directly in a sentence. The rules for placing commas in direct address are simple. If the name comes first, it is followed by a comma. Grandpa, I want to eat a truck-load of ice. Sam, I want to eat a truck-load of ice. If the name comes at the end of the sentence, the comma precedes the name. I want to eat a truck-load of ice, grandpa. I want to eat a truck-load of ice, Sam. If the name comes in the middle of the sentence, it is surrounded by commas. What I said, grandpa, is that I want to eat a truck-load of ice.What I said, Sam, is that I want to eat a truck-load of ice.

- 3

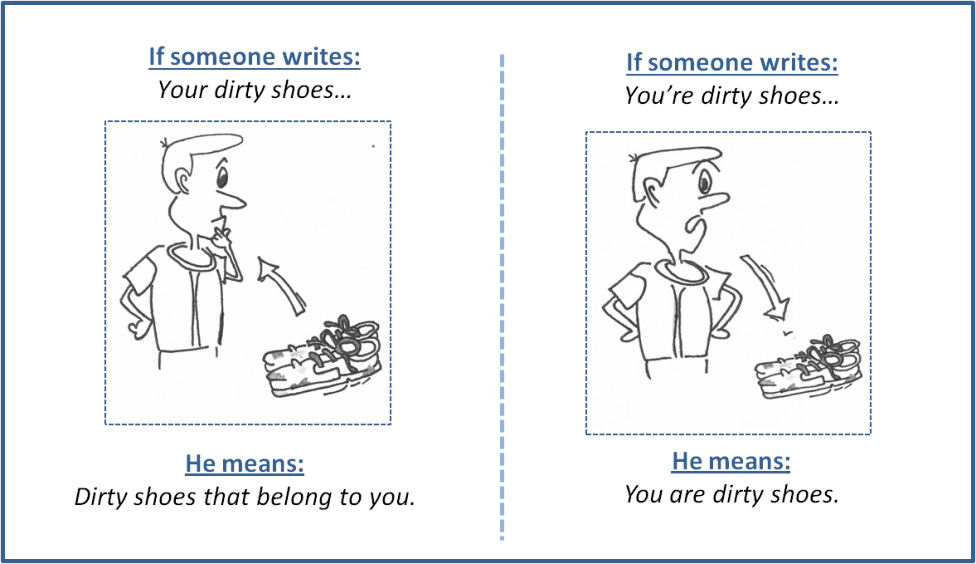

Your vs. You’re

I have gone through numerous lists of commonly confused words and in almost all of them your / you’re features in the top five. The error could stem in part due to an incorrect understanding of the use of apostrophes in forming contractions. The picture below should help them understand that the two words are different and should not be used interchangeably.

- By way of explanation, I use these points:

- You’re is a contraction of you are.

- Your shows possession. It means belongs to you.

- If you are confused on whether to use your or you’re, check if you are fits into the sentence; if it does, use you’re, else use your.

- 4

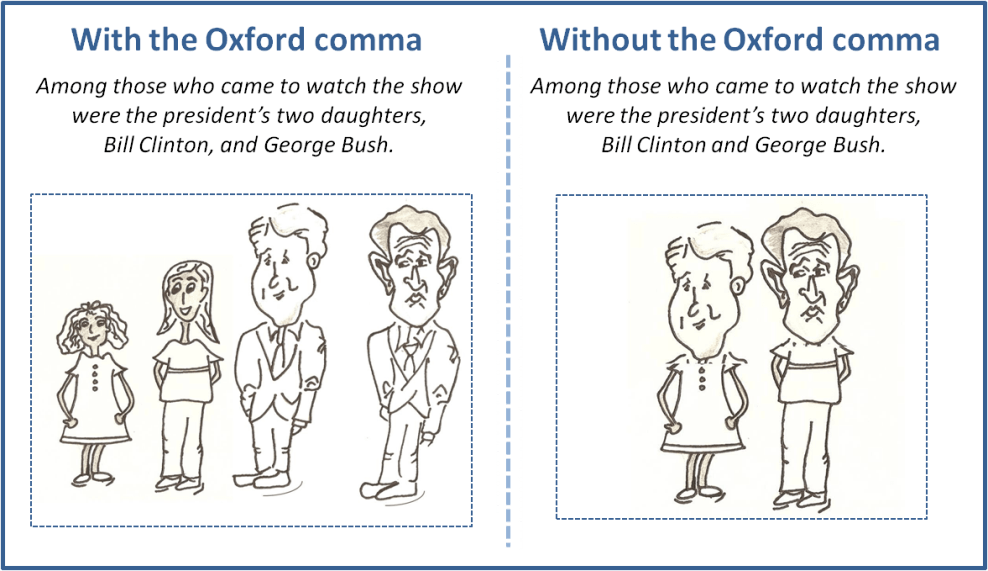

The Oxford / Serial Comma

The Oxford comma is a highly-debated topic among grammarians. While some feel that it is not necessary, others argue that leaving it out can cause confusion. If you are from the latter school of thought, then you can use the below picture to explain the rationale of using the comma to your students.

- By way of explanation, I use these points:

- The Oxford comma (also known as serial comma or Harvard comma) is a comma that is used before and/or in a list containing three or more items.

- I like to eat nails, glass, and shoes.

- I hate people who do not like to eat nails, glass, or shoes.

- In some cases, the Oxford comma helps avoid ambiguity in a sentence. In the second sentence of the picture, leaving out the comma before and may lead the reader to infer that Bill Clinton and George Bush are the two daughters of the president!

- The Oxford comma (also known as serial comma or Harvard comma) is a comma that is used before and/or in a list containing three or more items.

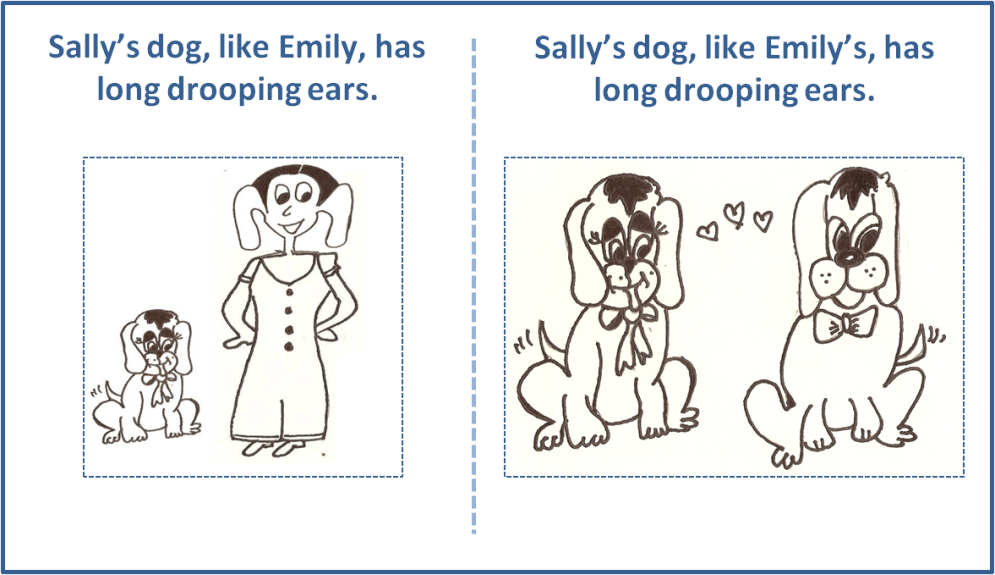

- 5

Faulty Comparisons

Faulty comparisons occur very frequently in writing. Most people do not even realize that they are comparing two things incorrectly. The picture below shows the confusion and humor that can be caused by faulty comparisons.

- By way of explanation, I use these points:

- Faulty comparisons occur when two things are compared inappropriately or in a way that could confuse readers / listeners.

- Often, the comparison will sound as though it's acceptable, but will be missing a few necessary words. The shirt you are wearing looks like my brother. Here, the shirt is being compared to the brother and not to the brother’s shirt. The shirt you are wearing looks like my brother’s. The shirt you are wearing looks like my brother’s shirt. Both of the above sentences are correct. In the first sentence, although the word shirt isn’t present, adding the ’s after brother implies that we are comparing the shirt belonging to the brother.

There are several benefits of using pictorial representations for teaching concepts of grammar, punctuation, and word usage.- Students appreciate the importance of the concept, as they can clearly see the confusion or humor caused by the error.

- Pictorial representations create visual reinforcement and can be especially useful for those students who are visual learners. If not anything else, students will remember the picture associated with each grammar lesson.

- The pictures can provide an element of fun to the learning process and take some of the boredom out of the grammar class.

5 Learning Strategies That Make Students Curious

Understanding where curiosity comes from is the holy grail of education.

Education, of course, is different than learning.

Education implies a formal, systematic, and strategic intent to cause learning. In this case, content to be learned is identified, learning experiences are planned, learning results are assessed, and data from said assessments play some role in the planning of new learning experiences. Learning strategies are applied, and snapshots of understanding are taken as frequently as possible.

This approach is clinical and more than a smidgeon scientific. It arrests emotion and spontaneity in pursuit of planning and precision, a logical trade in the eyes of science.

Of course, very little about learning is scientific. While data, goals, assessment, and planning should all play a role in any system that purports to actually accomplish anything, learning and education are fundamentally different. The former is messy and personal, painful and fantastic. The latter attempts to assimilate the former—or at least streamline it as much as possible in the name of efficiency.

An analogy might help.

learning:education::true love:dating service

True love may very well come from a dating service, and dating services do all they can to make it happen, but in the end—well, there’s a fair bit of hocus pocus at work behind it all.

Hubris and Education

Education is simultaneously the most noble and hubristic of all endeavors. This may all reek of sensationalism, but watch anyone at play, honing a craft, lost in a book, or engaged in a digital simulation and you’ll see a completely different person—one there physically, but far removed in spirit.

In a better place.

Causing this in a classroom is possible, but is as often the result of good fortune than good planning. The best substitutes that can masquerade as curiosity are dutiful compliance and engagement. Neither of these are curiosity, which has among its sources a strong sense of volition, accountability, and curiosity.

Here, let me try.

I want to show you what I can do.

I want to know.

And that last one—a sign of curiosity–is a bugger, one we’ve talked about before. Like the caffeine in coffee, the chords on a guitar, or the wet in water, genuine curiosity is not a thing, it’s the thing.

Not temporarily wanting to know, or being vaguely interested in an answer, but being able to put together past experience and knowledge like the millions of fibers on a network–only to be maddeningly stopped from branching further without understanding or knowing this one bit.

Like stopping an incredible movie right at the climax—that awful, crazy feeling inside would be unfulfilled curiosity—and it’d just kill you not to know. But where does it come from?

And can you consistently cause it in a learner?

If formal learning environments driven by outcomes-based systems have taught us nothing else, it’s that while we often can “cause” something to happen in learner, it is only by considerable effort, resources, and angst.

But we certainly can create ideal conditions where natural curiosity can begin to grow. What we do when it happens—and disrupts our planned lessons and tidy little units—is another story altogether.

5 Things That Make Students Curious

1. Old Questions

The simplest curiosities arise from old questions that were never fully answered, or that no attempt to answer was made.

Of course, any question worth its salt is never “fully answered” any more than a good conversation is ever finished, but as we learn and reflect and grow, old answers can look positively awkward, as they are bound by old knowledge.

Strategy to actuate: Revisit old questions—through a journal prompt, Socrative discussion, QFT (Question Formulation Technique), or even a fishbowl discussion. And also revisit the thinking from the first go-round to see what has changed.

2. Ambition

Ambition precedes curiosity. Without wanting to advance in position, thinking, or design, curiosity is simply a biological and neurological reaction to stimulus. But ambition is what makes us human, and its fraternal twin is curiosity.

Strategy to actuate: Well thought-out mentoring, peer-to-peer modeling, Project-Based Learning and a genuine “need to know.”

3. Play

A learner at play is a signal that there is a comfortable mind focused on a fully-internalized goal. It may or may not be the same goal as those given externally, but play is hypnotic and more efficient than the most well-planned instructional sequence. A learner playing, nearly by definition, is curious about something, or otherwise they’re simply manipulating bits and pieces mindlessly.

Strategy to actuate: Game-Based Learning and learning simulations like Armadillo Run, Fun, Civilization V, Bridge Constructor, and Age of Empires all empower the learner to play. Same with Challenge-Based learning.

4. The Right Collaboration At The Right Time

Seeing what is possible modeled by peers is powerful stuff for learners. Some may not be initially curious about content, but seeing what peers accomplish can be a powerful actuator for curiosity. How did they do this? How might I do what they did in my own way? Which of these ideas I’m seeing are valuable to me—right here, right now–and which are not?

Strategy to actuate: Grouping is not necessarily collaboration. To actuate collaboration, and thus curiosity, students must have a genuine need for another resource, idea, perspective, or something else otherwise not immediately available to them. Cause them to need something, not simply to finish an assignment, but to achieve the goal they set for themselves.

5. Diverse & Unpredictable Content

Diverse content is likely the most accessible pathway to at least a modicum of curiosity from learners. New projects, new games, new novels, new poets, new things to think about.

Strategy to actuate: Invite the learners to understand the need for a resource or bit of content and have them source it. Instant diversity class-wide, and likely divergence from where you were going with it all. At worst you’ve got engaged learners, and a real shot at curiosity.

Labels:

21st century learning,

digital learning,

education,

EFL,

ELT,

ESL,

ideas,

learning english,

learning strategies,

new teacher,

teaching english,

teaching tips,

teaching training,

thinking strategies

Individualisation in Language Teaching

This publication provides a useful introduction to innovative approaches to self-directed learning and individualisation: http://englishagenda.britishcouncil.org/milestones/individualisation-language-teaching

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)